2/1/2024

Postdoc Spotlight: Zack Wistort, Ph.D.

Studying the Sea from Space

By Bethany Augliere

Harmful algal blooms (HABs), like blue-green algae or red tide, happen when colonies of microscopic algae or bacteria grow out of control in the ocean or lakes. They’re troubling because they produce toxins that can:

- sicken or kill people and animals

- contaminate seafood

- create dead zones in the water where there is little or no oxygen which causes massive fish die-offs

- raise treatment costs for drinking water

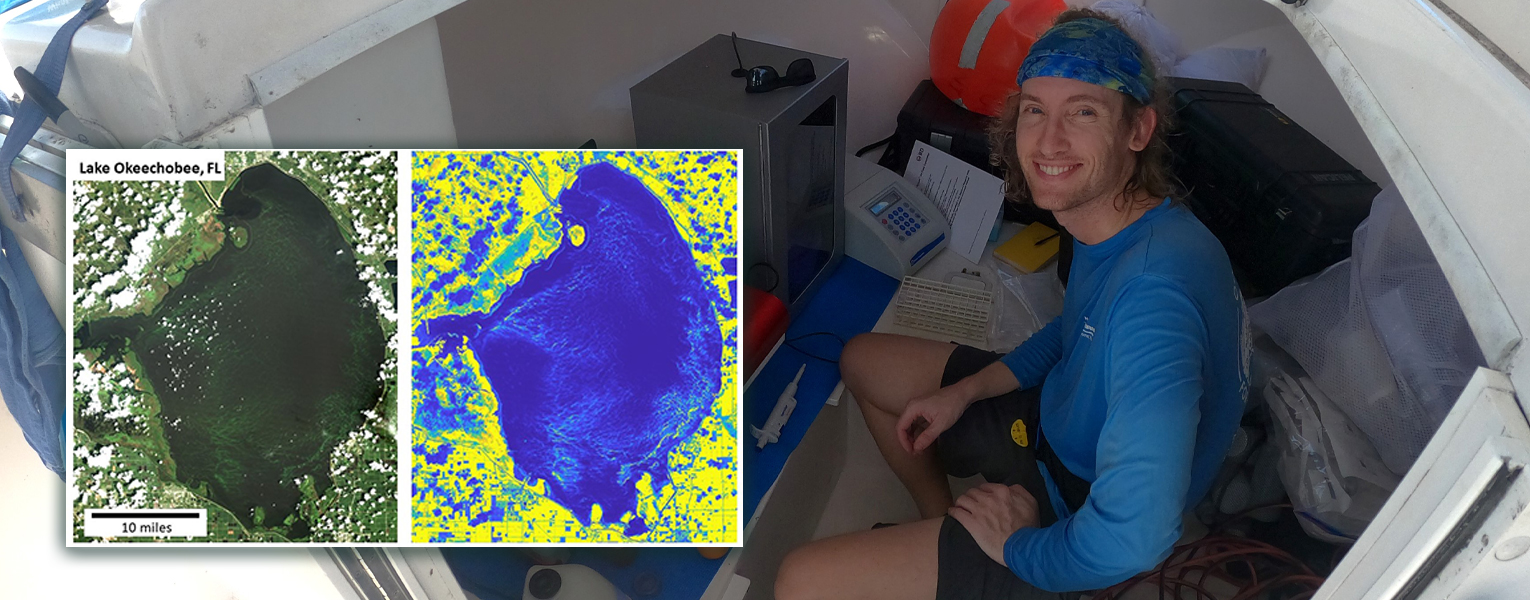

To learn more about how to stop these blooms, Zack Wistort, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at Florida Atlantic Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, is studying images of them captured from space.

Right now, 11,330 individual satellites in space circle the Earth, with a variety of uses from sending signals for the TVs in our homes, phones, internet and radio, to weather forecasting, navigation (GPS), and collecting data for scientific research, according to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs.

Scientists have used satellites to study blooms for 20 years, Wistort said. But satellites have been taking pictures of the Earth for 60 years, he said. In 1959, the U.S. satellite Explorer VI took the first photographic image of the planet Earth from space while passing over the Central Pacific Ocean. “Part of my work here is trying to figure out if we can use data from older satellites that weren't initially intended to make these measurements of harmful algal blooms,” he said. “And it turns out, you actually can.”

To study HABs from space, scientists use color. The satellite peers down at Earth’s surface and takes a picture, like a picture you might take with the camera on your phone, Wistort said. While a phone can only see three different colors, which are wavelengths of light, a satellite can see many different colors. HABs reflect back certain colors, so by measuring the amount and color of sunlight reflected from the water’s surface we can make maps of HABs. Today’s satellites are called multispectral, which means they can detect 10-20 different wavelengths of color, but satellites of the past were not as well equipped, said Wistort.

Looking at images of older satellites, and extracting what information he could from the photos, Wistort was able to use their images to map freshwater HABs, extending the record of harmful algal blooms back to the 1980s. From those results, he found that the algal blooms on Lake Okeechobee are occurring more frequently and growing larger.

More data over longer time periods mean more answers, Wistort said. “I think the cool part about having a longer record is now we have more bloom events that we can study to learn about how these blooms are growing and dying off,” said Wistort, who previously earned a doctorate and master’s degree in geology from the University of Utah. He also earned a bachelor’s in geology from the State University of New York College at Geneseo.

With the study of these images, he said, “we can start to really nail down the processes that drive bloom formation, which will help scientists and water management districts to fix the problem.”

If you would like more information, please contact us at dorcommunications@fau.edu.