2/21/2024

Science in Seconds: Studying Sounds

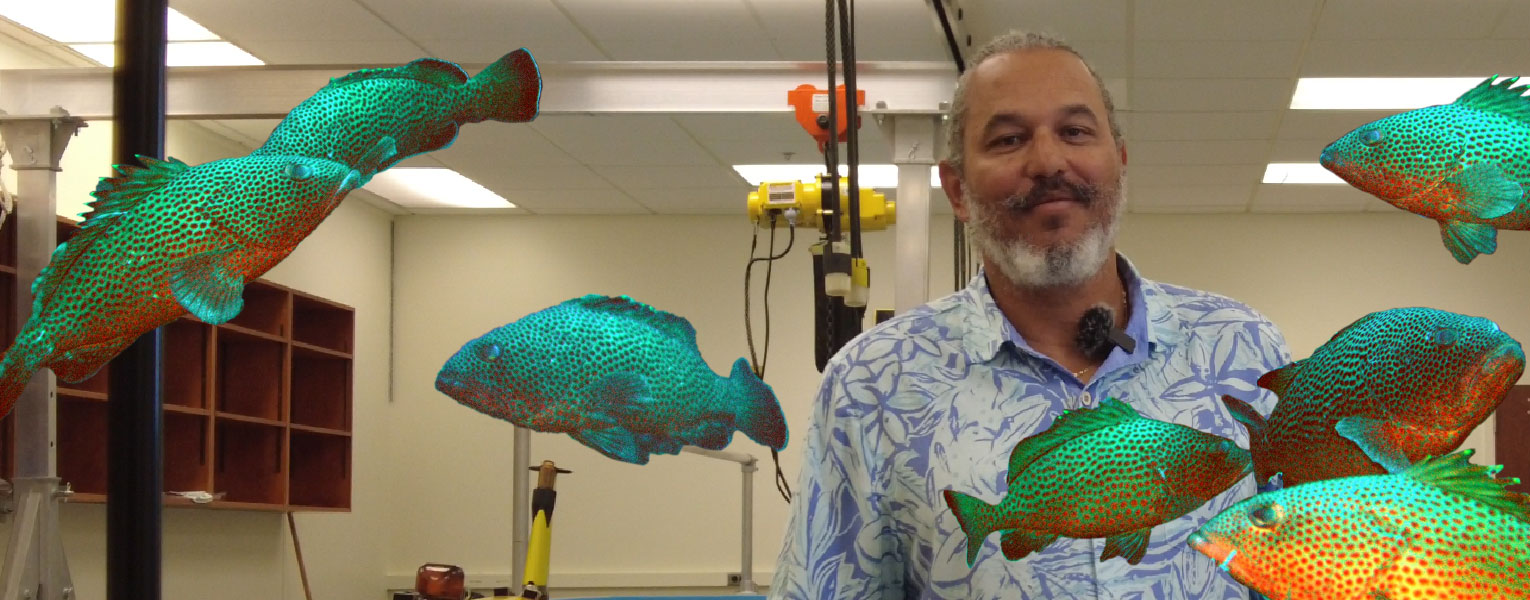

Using Grouper Mating Calls to Protect Them

By Bethany Augliere

When lots of groupers get together to mate under a bright full moon, they make special noises that help them find each other. But this also makes them easy targets for fishers and poachers.

“Groupers produce very distinct sounds associated with courtship, territoriality or reproduction. Some sounds are species-specific in frequency and pulse rate, which allows their signal to be clearly detected from acoustic recordings,” said Laurent Chérubin, Ph.D., a research professor at Florida Atlantic Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, who studied these sounds using special underwater microphones and clever computer programs to listen to where the groupers were making these noises. Chérubin wanted to find out where the groupers were mating and when.

He discovered that some places where groupers mate are important for certain types of groupers, like the Nassau and red hind groupers. But sometimes these places are not fully protected from fishing and other activities that harm the fish.

Research showed that groupers make these mating sounds in specific areas and at specific times, which can change depending on the moon phase. Chérubin also found that some groupers, like the red hind, might be mating in different places than previously thought, which means their protected areas need to be expanded.

Chérubin said it's important to understand how groupers move around and mate so we can help their populations grow. He said more areas should be marked off-limits to fishing during mating seasons to help the groupers thrive.

Using underwater microphones to listen to fish mating can be a useful and affordable way for scientists and managers to keep an eye on these vulnerable groupers in the future without interfering in nature.

“Passive acoustic methods do not interfere with grouper reproductive behaviors and may be a cost-effective alternative for managers or researchers monitoring various fish spawning aggregations simultaneously,” Chérubin said. “Moving forward, we hope to assess correlations between fish density and courtship-associated sound levels to explore the utility of acoustics as a sole mechanism for future studies, further reducing the effort required to identify and monitor these vulnerable fish spawning aggregations.”

If you would like more information, please contact us at dorcommunications@fau.edu.

The Power of Love Protects Groupers

Laurent Chérubin, Ph.D.

Florida Atlantic Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute

Watch video