11/3/2023

Cancer Center of Excellence: Fighting Back

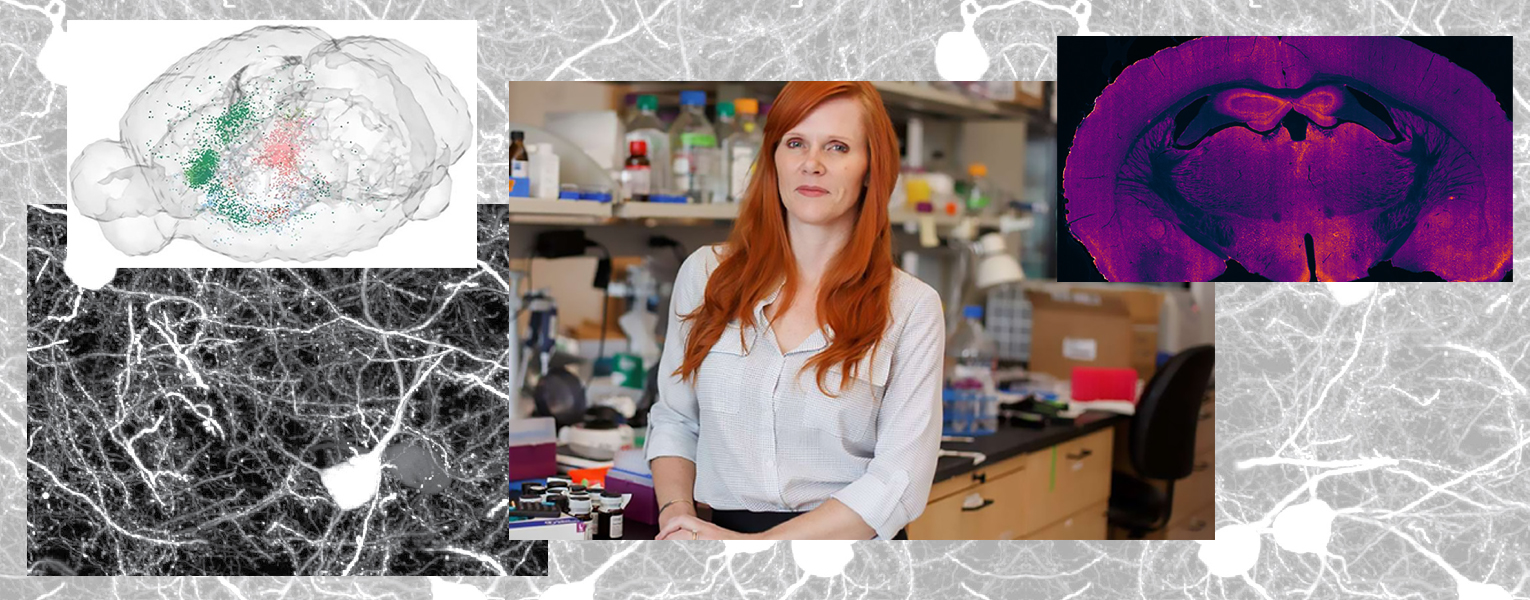

Researcher Develops Promising New Treatment for Brain Cancer

By Bethany Augliere

For people who develop glioblastoma, a type of aggressive and difficult-to-treat brain cancer, the five-year survival rate is 6.8%. By targeting a specific protein in the brain, Courtney Miller, Ph.D., a member of the Memorial Cancer Institute Florida Atlantic Cancer Center of Excellence, said she hopes to find better treatment options. “The current standard of care only extends lifespan by three to four months,” she said.

Miller, director of academic affairs and a professor at The Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology in Jupiter, as well as the co-founder of Myosin Therapeutics, has developed a compound, called MT-125, to attack glioblastoma cancer cells in two ways. It’s already showing promising results in mouse models, she said.

With glioblastoma, there are two problems to address when it comes to treatment. The first is proliferation, where “the tumor cells just divide like crazy,” she said. There’s also invasion, where the tumor cells migrate and invade the healthy brain tissue. Invasion is particularly problematic because you cannot remove the tumor with surgery without causing too much damage to the brain.

“Most therapeutics in development target preventing growth, but they don’t address the issue of cancer cells migrating throughout the brain,” Miller said.

The compound Miller and her collaborators are developing targets a protein called myosin. When MT-125 binds to myosin IIA, it prevents cancerous cells from altering their physical shape enabling them to spread to healthy tissue. MT-125 also alters the structure of myosin IIB, which prevents the tumor from growing by blocking cell division. This twopronged approach makes it different from other glioblastoma treatment options, Miller said.

It offers another benefit too. A common problem with treating cancer is developing resistance to treatment, whether it is chemotherapy or radiation. With Miller’s compound, it increases sensitivity to radiation.

Miller and colleagues are in the process of turning the compound into a drug. They’ve begun safety pharmacology studies, which examines the physiological impact of a substance in the therapeutic range and above. So far, it’s well-tolerated in mice with no dangerous side effects. “We’re feeling really confident about moving it forward,” Miller said. “Maybe early 2025 for a clinical trial.”

If you would like more information, please contact us at dorcommunications@fau.edu.