Fall 2025

Florida Atlantic: Sharkitecture

Unlocking the Hidden Engineering Inside a Shark’s Spine

Sharks have been perfecting their design for more than 450 million years. Unlike most vertebrates, they don't have skeletons made of bone. Instead, they rely on cartilage — mineralized, flexible and strong. And now, with the help of cutting-edge imaging and nanoscale analysis, researchers are discovering that these ancient predators have more than just brute strength working in their favor. They have architecture — or more precisely, "sharkitecture."

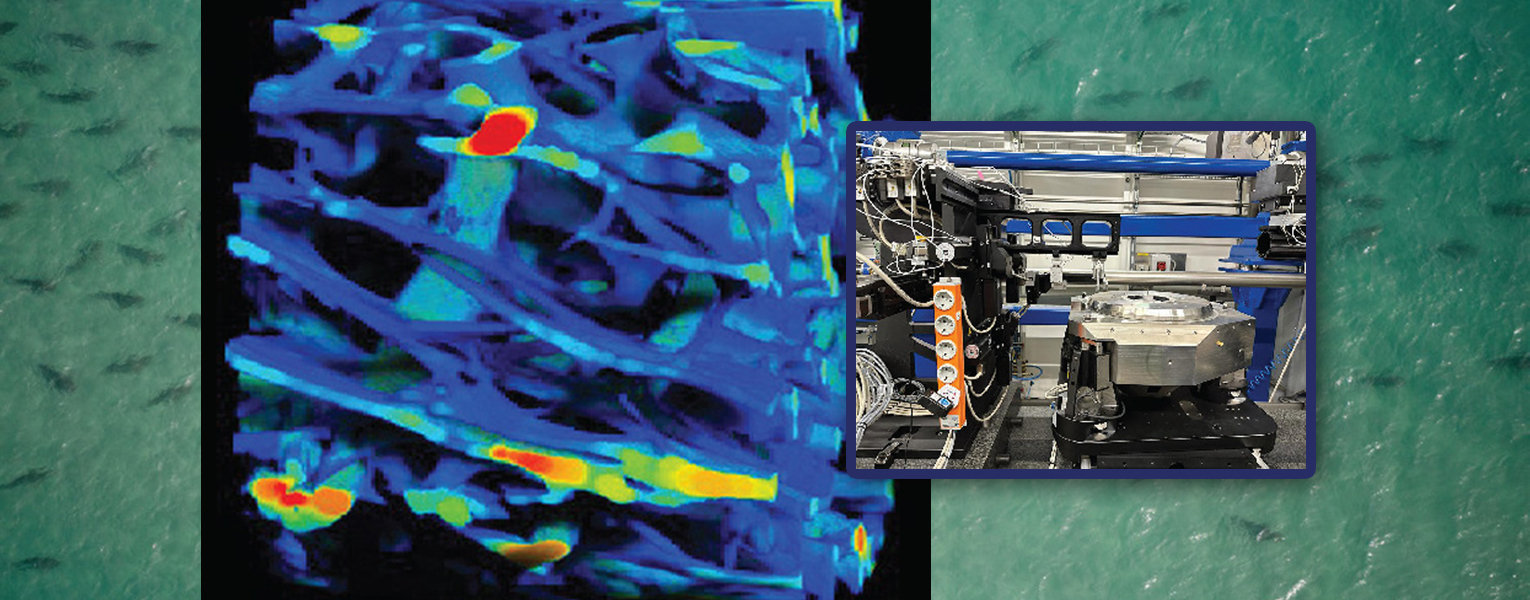

Florida Atlantic researchers peered inside the spine of the sleek blacktip shark and uncovered a microscopic structural design optimized for strength, flexibility and endurance. Using powerful synchrotron X-ray nanotomography and in-situ mechanical testing, the team revealed a stunning nanoscale blueprint that helps explain how sharks withstand the intense, repetitive stress of constant swimming.

Blacktip sharks are fast, agile hunters found in warm coastal waters around the world. Known for their bursts of speed — reaching up to 20 miles per hour — and their acrobatic movements, these sharks are constantly in motion. To maintain such power and grace, their skeletons must be both durable and flexible.

What researchers found inside their mineralized cartilage is remarkable. Two distinct regions within the vertebrae — the corpus calcareum and the intermediale — are made of the same materials (collagen and bioapatite, a mineral also found in human bones) but differ significantly in structure. In both areas, mineralized plates form porous frameworks reinforced by thick struts, designed to handle force from multiple directions. This makes the skeleton incredibly resilient, even under the strain of constant motion.

Even more striking: at the nanoscale, the team discovered that collagen fibers are tightly aligned with needle-like bioapatite crystals. This complex layered arrangement allows the cartilage to be tough without becoming brittle, a balance that's crucial for an animal in nonstop motion.

"Nature builds remarkably strong materials by combining minerals with biological polymers, such as collagen — a process known as biomineralization. This strategy allows creatures like shrimp, crustaceans and even humans to develop tough, resilient skeletons," said Vivian Merk, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Science, as well as in the Department of Ocean and Mechanical Engineering and the Department of Biomedical Engineering in the College of Engineering and Computer Science. "Sharks are a striking example. Their mineral-reinforced spines work like springs, flexing and storing energy as they swim. By learning how they build such tough yet adaptable skeletons, we hope to inspire the design of next-generation materials."

That spring-like quality is key. Sharks don't just power through the water — they store and release energy efficiently with each tailbeat. To better understand this, researchers subjected microscopic samples of shark vertebrae to mechanical stress. What they saw was incredible: after a single cycle of pressure, the material deformed by less than a micrometer. Only after a second round of loading did fractures appear, and even then, they were confined to a single mineralized layer, showing the structure's built-in resistance to catastrophic failure.

"After hundreds of millions of years of evolution, we can now finally see how shark cartilage works at the nanoscale — and learn from them," said Marianne Porter, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences in the Schmidt College of Science. "We're discovering how tiny mineral structures and collagen fibers come together to create a material that's both strong and flexible, perfectly adapted for a shark's powerful swimming. These insights could help us design better materials by following nature's blueprint."

That's the real promise of this research: using what sharks have evolved over eons to improve human technology today. The unique, fiber-reinforced architecture found in shark cartilage could inspire stronger, more flexible materials for medical implants, athletic gear, and protective equipment, offering strength without sacrificing adaptability.

In other words, sharkitecture isn't just about understanding sharks — it's about borrowing from their evolutionary success to build smarter, better designs for the future.

For more information, email dorcommunications@fau.edu to connect with the Research Communication team.