2025 Atlantic Storm Season Updates with Hurricane Expert Yijie Zhu, Ph.D.

Wednesday, Sep 17, 2025

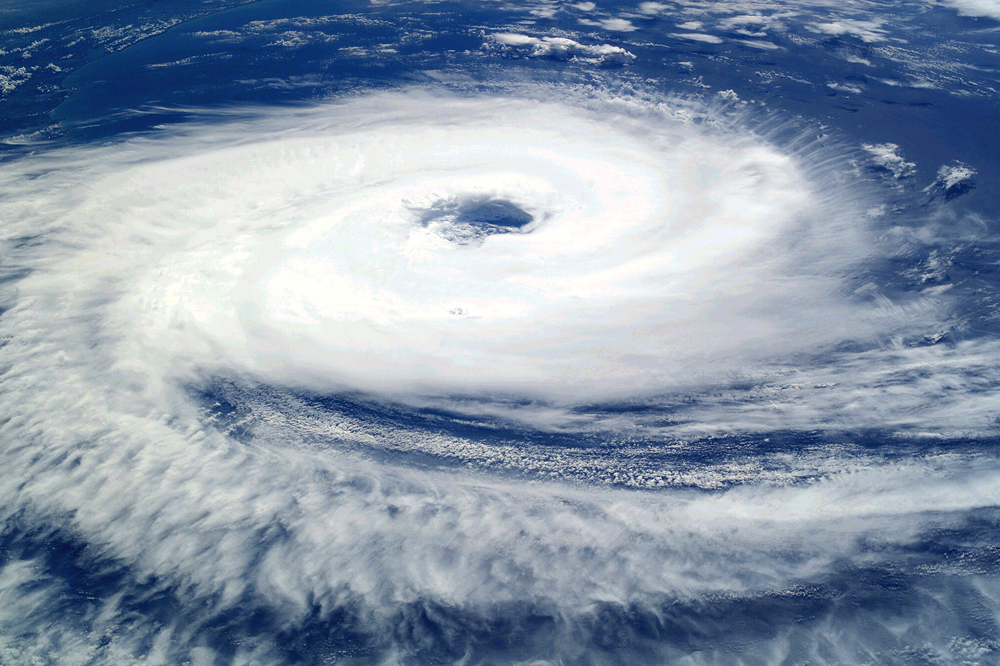

The tropics have been relatively quiet lately, but historically, 60% of activity occurs after September 10—the climatological peak of the Atlantic hurricane season. Forecasters are now turning their attention toward the western part of the Atlantic basin where more activity is typically seen moving into late September and October.

The tropics have been relatively quiet lately, but historically, 60% of activity occurs after September 10—the climatological peak of the Atlantic hurricane season. Forecasters are now turning their attention toward the western part of the Atlantic basin where more activity is typically seen moving into late September and October.

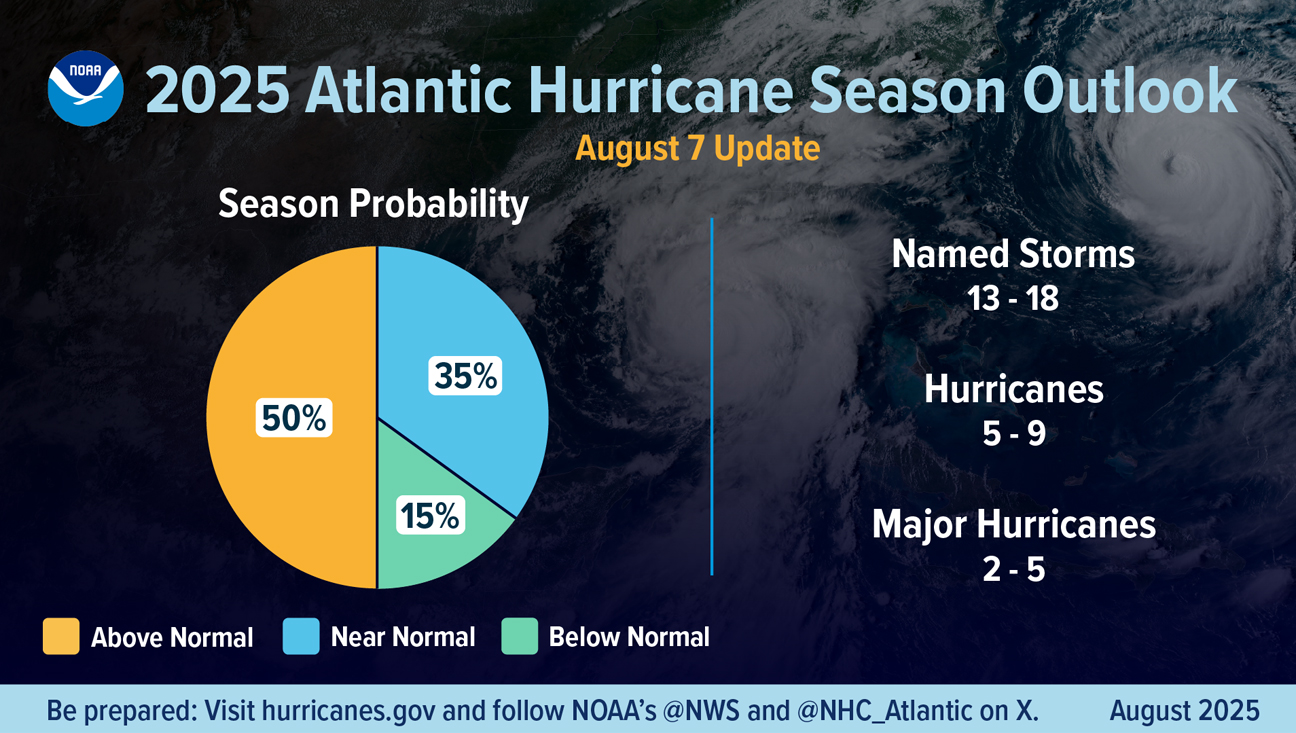

Forecasters from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Weather Service updated the 2025 seasonal forecast in early August, which predicted the likelihood of above-normal activity at 50%, a 35% chance of a near-normal season and a 15% chance of a below-normal season. The adjusted ranges are for the entire season from June 1 through November 30, and include the six named storms that have already formed. In the Atlantic basin, a typical hurricane season will yield 14 named storms, of which seven become hurricanes and three become major hurricanes.

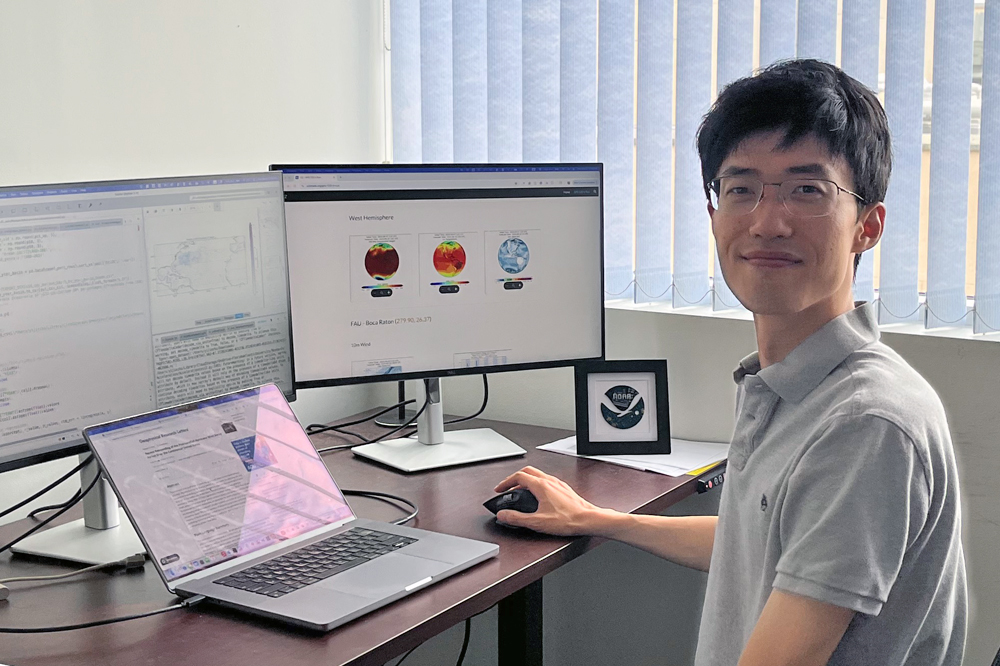

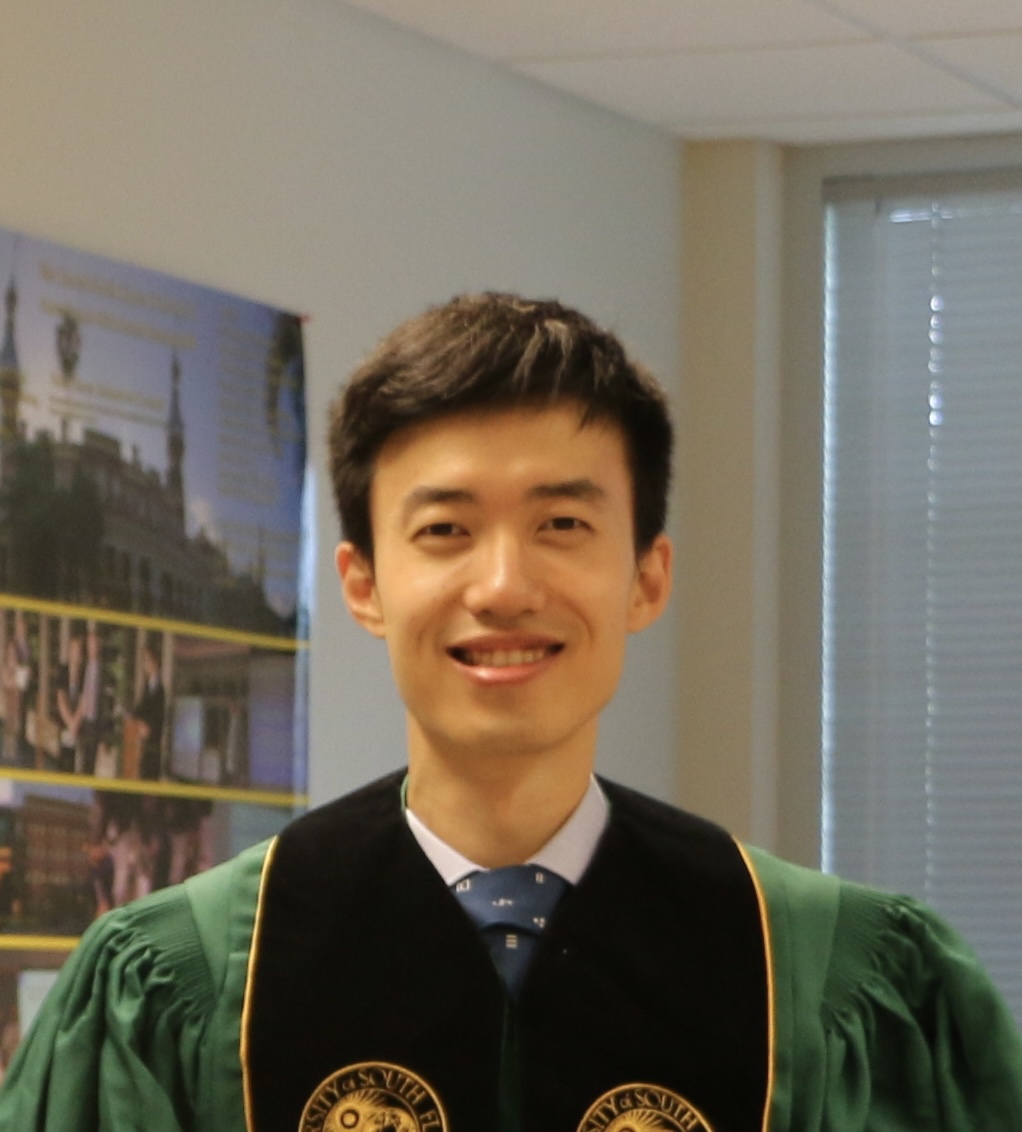

“We are stepping into the most active months of the hurricane season in Florida,” said Yijie Zhu, Ph.D., assistant professor, Department of Geosciences, Charles E. Schmidt College of Science at Florida Atlantic University. “It is important to note that the level of activity represents the overall hurricane activities, meaning they can be over the ocean without making landfall. We can also think of this reversely, even in a below-normal season, we could still have landfall hurricanes in our region that bring destructive damage.”

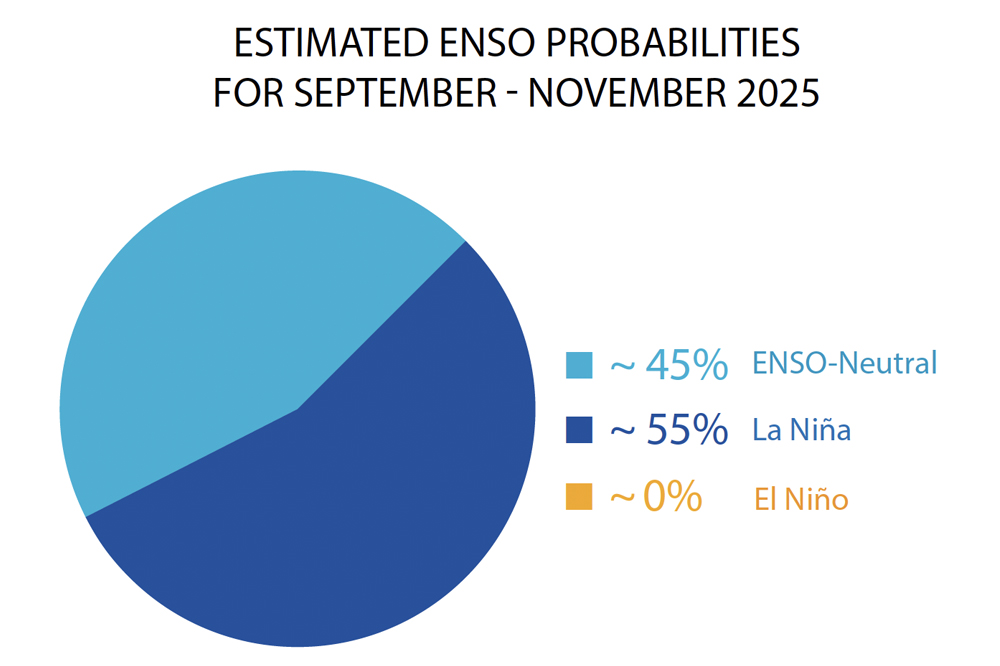

Over the past months, the climate was in El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) neutral conditions, with the sea surface temperature anomalies near average across the equatorial Pacific. ENSO-neutral conditions occur when ocean and atmospheric conditions in the tropical Pacific are near their long-term average, meaning neither El Niño (warmer) nor La Niña (cooler) is dominant.

“It is likely that La Niña conditions will develop for the remaining Atlantic hurricane season,” note Zhu. “This indicates favorable conditions, meaning reduced vertical wind shear—the change of wind direction and intensity with altitude—for hurricanes to form and intensify in the North Atlantic.”

Zhu’s research provides much-needed, critical information that is required to improve the weather models in forecasting storm intensity and wind radius changes during the post-landfall stage. He also stressed why it is important to make advances in weather models.

Zhu’s research provides much-needed, critical information that is required to improve the weather models in forecasting storm intensity and wind radius changes during the post-landfall stage. He also stressed why it is important to make advances in weather models.

“Weather models are our best tools for anticipating where storms will go and how strong they will become,” stated Zhu. “But most importantly, we use the results of weather models to interpret and assess what types of potential hazards we expect to face when they come our way. Even small improvements in the confidence of predicting storm intensity and tracks could lead to huge differences in how we allocate proper resources to different communities.”

Currently, Zhu’s research focuses on investigating historical hurricanes’ inland footprint, considering both post-landfall intensity decay and translation speed changes.

Currently, Zhu’s research focuses on investigating historical hurricanes’ inland footprint, considering both post-landfall intensity decay and translation speed changes.

“I am always fascinated by what happens when a hurricane makes landfall,” shared Zhu. “After all, science works to protect lives, economies and ecosystems, and how a storm’s intensity changes during and after landfall is the most critical part, in terms of hazard preparation and mitigation.”

Looking ahead to next year’s storm season, the forecast looks to be quite uncertain.

“There is likely some degree of La Niña-like signals in late 2025 to early 2026,” stated Zhu. “If the La Niña condition persists, we may need to prepare for a very active season in 2026. What is certain is that the first storm of the 2026 season will be named Arthur.”