Dual Brain Waves Fine-tune the Sense of Place

As you walk into a room, the neurons that draw your internal maps of the world are primed and ready to fire bursts of signals to nearby cells, joining in on the electrical and chemical processes that underlie our complex ability to understand where we are and how to get around.

These “place cell” neurons in the hippocampus are listening in for specific, relatively slow brain waves called theta waves. When a wave comes in at the right frequency, the cells respond with a rapid burst of activity.

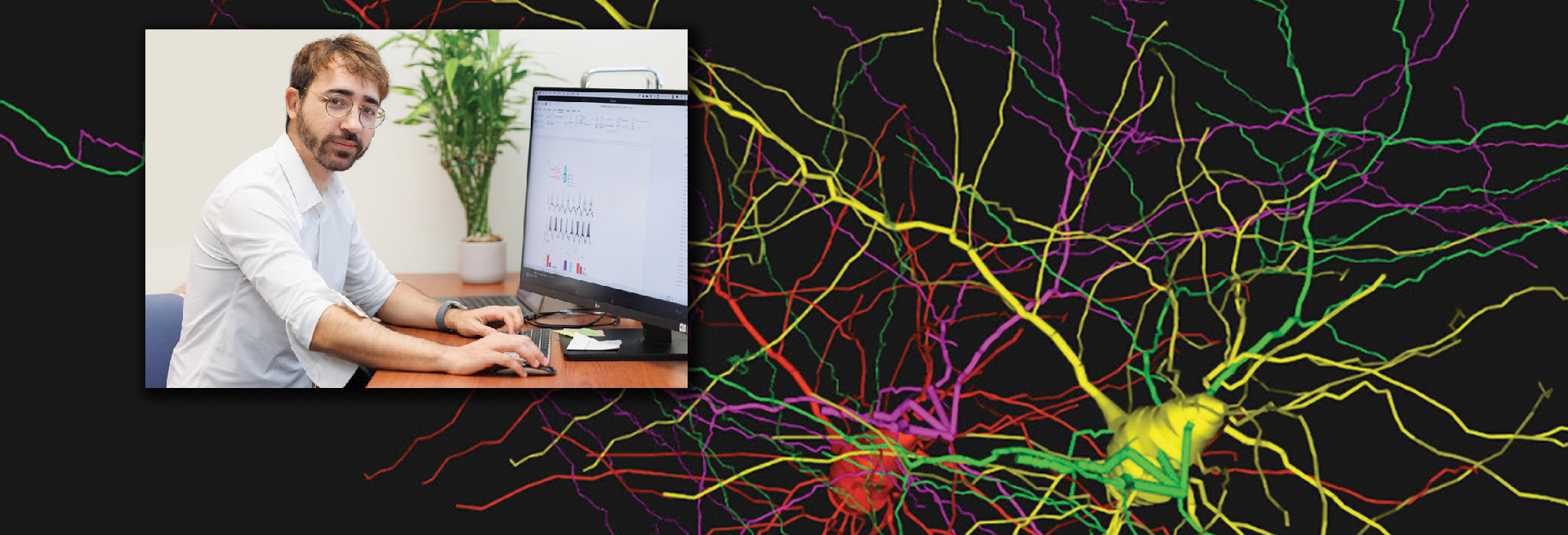

The link between theta waves and entering a location is a recent discovery from neuroscientists including Rodrigo Pena, Ph.D. an assistant professor of biological sciences in Florida Atlantic University’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Science and a member of the Stiles-Nicholson Brain Institute.

The researchers also found that place cells are tuned for faster brain oscillations, known as gamma waves. These are associated with leaving a location and trigger single spikes of activity instead of bursts.

This is an example where resonance in neurons has an important role, Pena said, where cells are tuned to a particular frequency and can fire more if they encounter it. “It turns out that place cells can do that very well for frequencies like gamma and theta,” Pena said. “There seems to be a code where we have oscillation frequencies amplified when animals enter or leave the place field.”

Pena and his collaborators have further built on these findings in a new paper published in the journal PLOS Computational Biology. They’ve shown for the first time that a single place cell neuron can be “double-coded” for multiple brain waves, responding to each frequency with a different spike mode.

“Because we have this interplay between gamma and theta waves and the animal entering a field and leaving a field, it seems that in the same signal, you have interleaved resonance,” Pena said. “You have two types of resonance happening at the same time. Neurons respond either to single spikes or bursts depending on the gamma or theta frequency.”

The study further shows that these tunings are controlled by the neuron’s internal characteristics, including its ionic currents. These control the flow of cellular electrical signals through the movement of charged particles like potassium or sodium ions across membranes.

These new insights into the brain’s informational handling could inform research of disorders of disrupted brain rhythms like epilepsy.

“The better we understand how neurons work — what we like to call the neural code — the better we can manipulate them,” Pena said. “Everything that’s tied to memory or spatial navigation can be tuned by those ionic currents, which you can also change with pharmacological interactions.”

The research was funded in part by the Program in Computational Brain Science and Health, which is sponsored by Palm Health Foundation. Pena, a computational neuroscientist, said the field creates new opportunities in brain research by connecting techniques and specialties that otherwise operate at completely different scales.

“You can create models that can crosstalk between those different levels of organization in the brain,” Pena said. “This is why this work was successful, because we managed to do something at the level of an ion channel and connect it to behavior.”