Breakthrough Reveals Contribution of Disrupted Copper Balance to Gene Defect Produces Neurodegeneration

An intriguing gene that brain scientists have tracked for 10 years from roundworms to rodents has been shown for the first time to control key aspects of basic cell physiology, according to new research led by Florida Atlantic University.

The mechanism by which the enigmatic gene sustains energy production, suppresses oxidative stress, constrains neuronal hyperactivity, and wards off age-dependent neurodegeneration was revealed by a team of scientists headed by Randy D. Blakely, Ph.D., executive director of Florida Atlantic’s Stiles- Nicholson Brain Institute.

The gene, known as swip-10 in the roundworms in which it was first discovered, carries out a key enzymatic reaction to support the function of mitochondria, the cell’s energetic powerhouse. Blakely and colleagues found this mitochondrial support depends on the gene’s regulation of a biologically active form of the micronutrient copper. Without the protein encoded by the gene, the health of neurons suffers and other cells show significant signs of stress.

As Blakely and collaborators first elucidated the identity and function of the gene after its discovery in 2015, geneticists found that a reduction in the human version of the protein led to increased risk for a common form of Alzheimer’s disease. The chemical pathway described in the new research may therefore provide new opportunities for the development of new medications to treat Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, that display alterations in mitochondrial function.

This breakthrough, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, "provides a cogent example of how research in a simple organism can lead to discoveries with relevance to human disease, owing to the conservation of genes and biochemical pathways across millions of years of evolution," Blakely said.

"Although roundworms appear at first glance to have little in common with humans, their simple nervous system expresses many of the same genes that build the marvelously complex brain we use to think, feel and dream," he said. "Stepwise, we figure out how genes work in simple systems and then pursue the actions of related genes in more complex organisms like mice and rats whose nervous systems are more like ours, ultimately gaining insights into how the human brain works, and why sometimes, it fails."

The identification of this gene began with investigations into how another powerful brain chemical, dopamine, is controlled. Blakely grasped the power of a genetic model of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) — a common tool of neuroscientists, including multiple Nobel laureates — to illuminate fundamental mechanisms that support neural signaling and health. Worms are known to use dopamine to control movement, reminding Blakely that loss of dopamine in the human brain leads to impaired movement associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Blakely and postdoctoral fellow Lankupalle Jayanthi, Ph.D., now associate professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, first cloned the C. elegans gene that encodes the dopamine transporter protein. The human version of this protein is well known to neurobiologists as responsible for the addictive actions of cocaine.

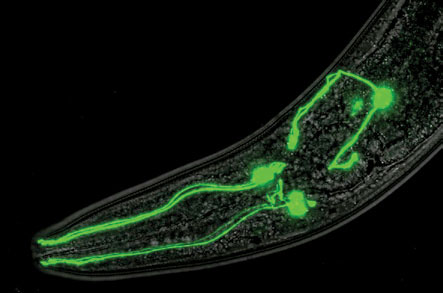

Next, Blakely lab postdoctoral fellow Richard Nass, Ph.D., associate professor at Indiana University School of Medicine, hooked a fluorescent molecule to the worm transporter gene.

Through the worm’s transparent body, scientists could for the first time visualize dopamine neurons in a freely moving animal.

"These early steps, taken more than 20 years ago, were very exciting," Blakely said. "But we saw a bigger prize ahead if we could come up with an easy way to identify new genes whose loss would disrupt the function or health of dopamine neurons. Then we might have new leads on human disorders where dopamine function is disrupted as in Parkinson’s disease or addiction."

Later, Shannon Hardie, Ph.D., a former Blakely Lab member and current interim dean at the Kinkaid School, discovered that worms lacking the dopamine transporter are almost immediately paralyzed when they are put into water, whereas normal worms can swim vigorously for an hour. The team called this loss of swimming capacity "Swip," named for their swimming-induced paralysis.

Just as important, Hardie found that swimming paralysis could be entirely reversed if normal dopamine signaling was restored.

Swip was the simple, dopamine-dependent behavior Blakely had been looking for as a means to identify genes that support the signaling and health of dopamine neurons. Former lab member Andrew Hardaway, now assistant professor at University of Alabama-Birmingham, then screened mutant worms for emergence of Swip, identifying a numbered collection of genes whose mutation caused the production of altered proteins, including one labeled simply as SWIP-10.

When analyzing the SWIP-10 protein, Hardaway and Blakely found it was highly related to another protein known to carry a particular fold in its structure. Notably, the alterations in SWIP- 10 found by Hardaway to cause paralysis were found in this same fold.

When Blakely’s graduate student Chelsea Gibson, now at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, found that SWIP-10 mutant worms lost several classes of neurons as they age, including those that make dopamine, the idea that the human equivalent known as MBLAC1 might underlie some forms of neurodegenerative disease seemed likely.

She also observed the telltale signs of oxidative stress, a feature thought by many to cause or accelerate human neurodegenerative disease.

"Finding out that MBLAC1 was a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease really got the motor running and has shifted a significant fraction of our work to pursuing SWIP-10 and MBLAC1 in parallel to gain further insights into neurodegenerative disease," Blakely said.

For example, Blakely’s group has created mice lacking MBLAC1. Preliminary studies have found that their brains exhibit an elevated level of beta-amyloid plaques — a major molecular hallmark of Alzheimer’s — when the mice are engineered to carry other mutations found in the disease.

"This finding is quite promising, as many risk factors for lateonset Alzheimer’s disease are not believed to cause the disorder themselves, but rather to accelerate or magnify pathological events triggered by other changes," he said.

So how does loss of SWIP-10 (and presumably MBLAC1) lead to neurodegeneration? Blakely and recently graduated doctoral student Peter Rodriguez reasoned that the enzymatic action of MBLAC1 must hold clues. They connected the dots between two seemingly unrelated studies from other labs.

The first described an enzymatic activity for MBLAC1. The second revealed a surprising path from the product of that enzymatic activity to a form of the essential micronutrient copper. The Florida Atlantic team reasoned that if MBLAC1 could be linked to the regulated balance of the levels of two copper ions in the body, then worms lacking SWIP-10 should follow suit.

Indeed, Bakely Lab experiments showed these animals demonstrated significantly lower levels of the beneficial copper ion, diminished mitochondrial function, lowered ATP levels, and increased oxidative stress. Importantly, these functions, as well as the neurodegeneration seen in prior studies, were restored by genetically augmenting SWIP-10 mutant worms with copies of functional SWIP-10, and by pharmacologically elevating levels of the beneficial copper ion.

This new understanding of the mechanism between SWIP- 10, MBLAC1 and copper has shown the researchers points in a chemical pathway that may prove to be therapeutically beneficial, Blakey said. The work has led to an international patent application by Blakely’s team in hopes of securing the investments needed to expand and translate the SWIP-10 and MBLAC1 findings into improved diagnostics or therapeutics for neurodegenerative disease.

"Neurons and other cells in the brain harbor secrets that will take us hundreds of years, if not longer, to sort out, and there are surprises all along the way that can be targets for new interventions," Blakely said. "I am certain that there will be a back and forth between the worm and the rodent and the human brain as we capture the opportunities that each gives us to help people who suffer from devastating brain disorders."