Faces of Addiction

Over the past two decades, opioids — in the form of prescription painkillers, heroin and illicit fentanyl — have contributed to nearly 400,000 overdose deaths in the U.S. It is impossible to calculate the suffering these drugs have caused.

“Opioid addiction is a disease, and what we have seen in much of the nation is truly an epidemic,” said Jennifer Attonito, Ph.D., instructor in health administration in the College of Business, who studies policy related to addiction. “It’s been pervasive in life in the U.S., and uniquely so in Palm Beach.”

Palm Beach County became a hotbed for a fraudulent treatment industry, and it has ranked among the state’s worst in opioid-related deaths. A former substance abuse therapist who has lived in Delray Beach and Boca Raton, Attonito watched the epidemic flourish in her own backyard. Now, she and others are working to uproot it.

Attonito serves on the State Attorney’s Sober Homes Task Force, which, through arrests, new laws and regulations, has begun to successfully address the county’s crisis. She is also among 40 faculty and staff whose efforts are united by FAU’s Addiction Research Collaborative.

Some of these researchers investigate addiction and potential treatments in labs, while others go out into the community. Their work with those affected by opioid abuse, or at risk for it, illuminates the epidemic’s human toll as well as reasons for hope — in Palm Beach and beyond.

When Niki Dietrich, right, remembers her struggle to reunite with her toddler, she thinks of the Palm Beach International Airport. Once or twice a month for half a year, Dietrich flew back to her native New Jersey to see her daughter, who was in her sister’s care, and to deal with the custody case.

After about a decade in and out of jail, psych wards and treatment for heroin and alcohol abuse, Dietrich had at last built a stable, fulfilling life in Lake Worth, Fla., and hoped to make her toddler part of it. But the judge, and her sister, resisted.

“They were not willing to accept me relocating to Florida, and I really truly believed what I was doing was right,” she said. “I talked to a lot of people and I prayed about it.”

Dietrich, 30, is one of three women given a handheld digital camera by Heather Howard, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Phyllis and Harvey Sandler School of Social Work. All three are mothers coping with an opioid use disorder — the medical term for an addiction — who lost custody of their children. Howard and her collaborator, Marianna Colvin, Ph.D., also an assistant professor of social work, asked the women to document their experiences with the cameras and to envision change within the system that separated them from their children.

Howard studies the quagmire that women like Dietrich face: Pregnancy and the mother-child bond can offer powerful motivation for positive change. However, deeply ingrained stigma can make it difficult for them to ask for and receive support. Often, these mothers become entangled in a child welfare system that is prone to separate them from their children — with potentially negative consequences for both mother and child, Howard said.

“Much of my research focuses on the mother-infant dyad. Instead of polarizing an infant from the mother, we should be thinking about how we can we keep this mother and infant as a unit,” Howard said.

In another project, she is tracking mothers with opioid use disorders after they are released from incarceration, and she plans to study the effectiveness of offering mothers peer support in long-term recovery. She and Colvin are recruiting more participants for the photography study.

After Dietrich refused to return to New Jersey, proceedings to terminate her parental rights began. But a caseworker intervened, even chaperoning visits to help Dietrich bond with her daughter. Dietrich and her daughter now live in Lake Worth.

The other two mothers in the photo study group did not have such positive experiences. Discussions sparked by their photographs led the three women to decide to share their perspectives directly with the child welfare workers charged with deciding to remove a child, and others, like family court attorneys, who become involved later.

“My ultimate goal is that women are informed, that they can feel empowered to advocate for themselves and deal with child welfare systems, that they can heal from trauma,” Howard said.

After two arrests for possession of cocaine, Tracy Meredith naturally wanted to avoid felony charges and prison. So, she agreed to a two-year-long drug court program, a decision she regretted at first.

“As a get-out-of-jail-free card, it was appealing to me. I was desperate,” she said. But the opportunity was anything but free. Drug court programs are intensive, and hers, in DeKalb County, Georgia, is especially so. In the beginning, it dominated her life with drug screens, nearly day-long classes, and constant threat of jail.

“I used to think all the time, what did I get myself into, I cannot do this,” Meredith said.

For people like her — who have committed nonviolent crimes to feed an addiction — drug courts offer a deal: Complete strictly supervised treatment and training programs, and your charges will be dropped. “An arrest can be an opportunity for the criminal justice system to intervene in a positive way,” said Wendy Guastaferro, Ph.D., associate professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice. “The pendulum swings between punishment and rehabilitation. Drug courts have demonstrated their effectiveness, and that has helped keep the momentum on the side of rehabilitation.”

Guastaferro studies best practices within these courts, such as efforts to improve parenting skills and the match between courts’ offerings and participants’ needs. She arrived at FAU in August of 2017; her recent research has focused on Georgia drug courts, including DeKalb County.

Meredith graduated in 2014, and now calls drug court “divine intervention.” Without her arrests, she said, “I don’t think I would have gotten help.” (She did not participate in Guastaferro’s studies.) The share of drug court participants with opioid addictions has increased, Guastaferro said. Even so, few drug courts offer medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which prevents the agonizing withdrawal that occurs when someone with an addiction stops using opioids. Guastaferro is examining the issue at a broader scale, looking at how frequently those involved in the criminal justice system get MAT if needed.

“MAT can save lives, first and foremost. Helping people physically is as important as helping them with social services,” she said.

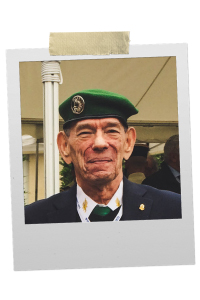

For Mark Yarry, right, many years of addiction to prescription painkillers meant a fixation on time. “What happened was it made my watch the most important part of life,” said the 79-year-old Boca Raton resident. “Every four hours, I was waiting, watching my watch to take another pill.”

Aging often brings aches and pains. But the treatment many seniors receive — painkilling opioid prescriptions — can create new problems, including the risk of dependence.

“Seniors are different. They are not going out to the street to get heroin or fentanyl,” said Juyoung Park, Ph.D., associate professor in the Phyllis and Harvey Sandler School of Social Work. “They have pain, perhaps from osteoarthritis, then they get a prescription. They get addicted later.”

Long-term use of opioid pills increases the risk of addiction, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Seniors may misuse their prescriptions to cope with isolation and depression, heightening the danger, Park said.

While a doctoral student in Baltimore, she studied misuse among seniors who, like Yarry, suffered from chronic pain. “A lot of people said, ‘I don’t know how to manage my pain without taking medication,’” Park recalled.

Yarry, who has not participated in Park’s research, began taking pain medication after being injured while fighting in the French Foreign Legion nearly 60 years ago. Decades later, he developed osteoarthritis in his hands, then spinal stenosis, and his dosage increased. In fall of 2017, he went off the drugs cold turkey, an excruciating 11-day ordeal. Yarry now uses topical patches to soothe his hands.

Park studies another alternative: exercise. To treat chronic conditions, seniors average five to six daily medications. Such regimes create a risk of harmful drug interactions while stressing the liver and kidneys, she said. While opioid painkillers add to the dangers, exercise does not.

In a recent study, she and colleagues found that chair yoga, modified for seniors, can reduce pain and improve physical function among those with osteoarthritis, a common form of joint degeneration. Participants taking pain medication, including opioids, said they were able to cut back on pills. “We don’t want to see seniors addicted to medication,” Park said. “Certain types of exercise may help prevent that.”

FAU scientists, like those listed below, are parsing the biological underpinnings of addiction to better understand and treat the disease.

• Randy Blakely, Ph.D., studies a class of brain proteins that clean up chemical signals called neurotransmitters. Drugs, including cocaine and amphetamines, target these so-called transporter proteins. His lab is exploring the pathways by which these drugs achieve their effects in order to intervene and potentially treat addiction. Blakely is the executive director of the FAU Brain Institute and a professor of biomedical science in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine.

• Lucia Carvelli, Ph.D., uses a worm as a simple model to study how amphetamines stimulate the brain’s reward system. She has found that fetal worms exposed to these drugs were more sensitive to them as adults, a change they passed on to the next generation. This discovery has implications for understanding the human predisposition to addiction. Carvelli is an associate professor of biomedical science at the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine and a member of the FAU Brain Institute.

• Predrag Cudic, Ph.D., is developing a new type of opioid-based pain medication that does not have the side effects and risk of addiction associated with conventional opioid painkillers. He has designed new analgesic molecules and a strategy for delivering them to their targets in the brain via an intranasal spray. Cudic is a professor of chemistry and biochemistry in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Science and an FAU Brain Institute member.

• Janet Robishaw, Ph.D., is using data from 25,000 patients receiving opioids for chronic pain to identify the genetic variants linked to a high risk of addiction. By creating an “addiction risk score,” she hopes to help doctors identify the 20 percent who are predisposed to addiction before they are given prescriptions. Robishaw is a professor and senior associate dean for research in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine and a member of the FAU Brain Institute.

• Lawrence Toll, Ph.D., investigates the signaling systems within the body that respond to opioids, whether they are drugs or molecules it produces naturally. He explores the biochemical basis for pain and drug addiction, and he is currently working on potentially less addictive pain treatments and new medications for drug abuse. Toll is a professor of biomedical science in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine and an FAU Brain Institute member.

If you would like more information, please contact us at dorcommunications@fau.edu.

Larry Toll, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical science in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine and a Brain Institute member, talks about the science behind addiction.

What is addiction?

“Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain. It is considered both a complex brain disorder and a mental illness. Addiction is the most severe form of a full spectrum of substance use disorders, and is a medical illness caused by repeated misuse of a substance or substances.” - National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

What do opioids do to a person’s brain? Opioids do many things in many parts of the brain. Opioid receptors are found in brain regions involved in pain, respiration and reward, among others. In pain regions, opioids prevent pain signals from reaching the brain and from reaching peripheral sites, such as hands and feet, that sense the pain. In brain centers that keep you breathing, opioids block activation. This is why opioids cause respiratory depression and death by overdose. “Nearly all addictive drugs directly or indirectly target the brain’s reward system by flooding the circuit with dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter present in regions of the brain that regulate movement, emotion, cognition, motivation and reinforcement of rewarding behaviors. When activated at normal levels, this system rewards our natural behaviors. Overstimulating the system with drugs, however, produces effects which strongly reinforce the behavior of drug use, teaching the person to repeat it,” according to NIDA. Ultimately chronic use causes poorly understood brain changes that lead to tolerance development to both its pain reducing activity and its rewarding activity, leading to a requirement for increased drug use. It also causes poorly understood changes that perhaps permanently modifies the reward system leading to a potentially lifelong relapse risk.

How quickly could someone become addicted? Addiction is considered approximately 50 percent environmental and 50 percent genetic. This means that different people will become addicted at different rates, and some people not at all. This is not to say everybody won’t become dependent. Dependence means you will go through withdrawal. Everybody will do that after taking opioids for a moderate amount of time, and the longer you take them, the worse the withdrawal will be. Opioid withdrawal is bad and can lead to relapse. But that is not addiction.

Why is it so difficult to treat addiction? Again, addiction causes real changes in the brain that leads to compulsive drug taking and poor decision making. There is evidence in the literature that it changes your reward “set point.” In other words, you may feel bad “dysphoric” without drugs once becoming addicted. So, people take the drugs to feel normal. There is some reason to believe that some people take drugs in the first place because the drugs make them feel “normal” for the first time. These people probably become addicted more quickly or easily.